New Images for an Old Ceremony

Bernd Stiegler

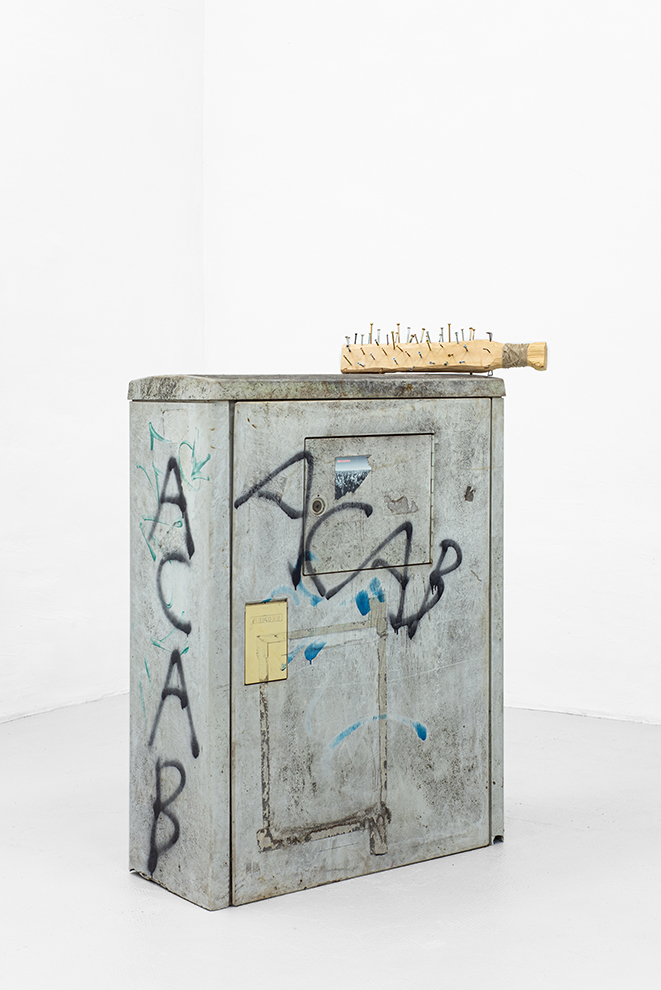

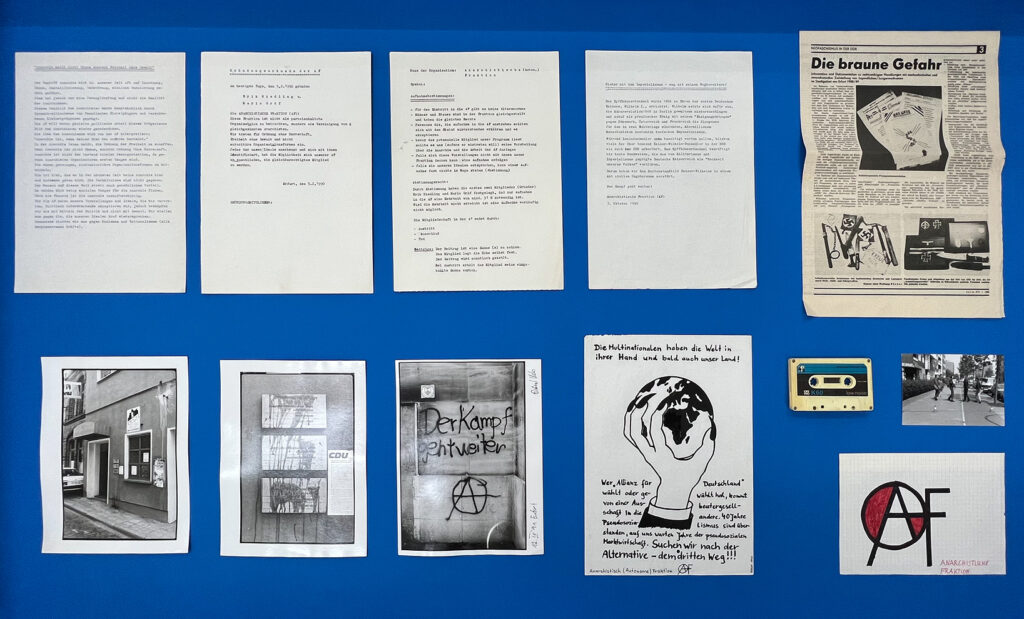

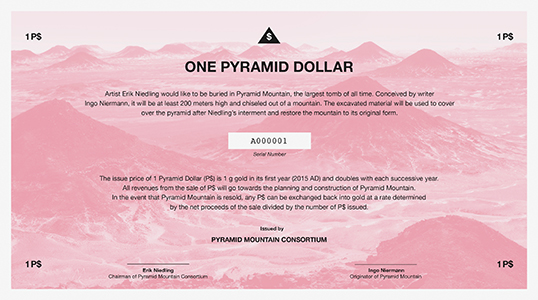

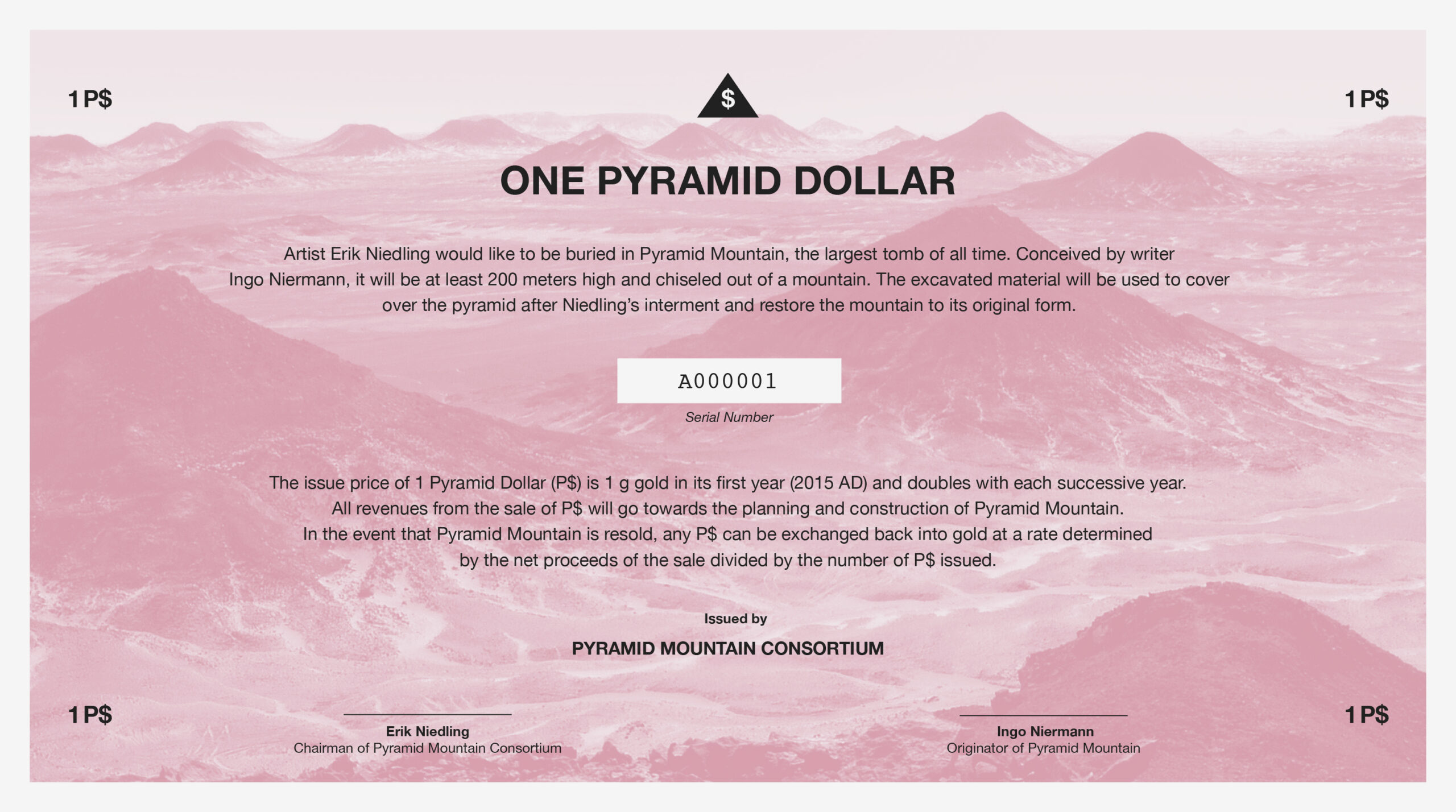

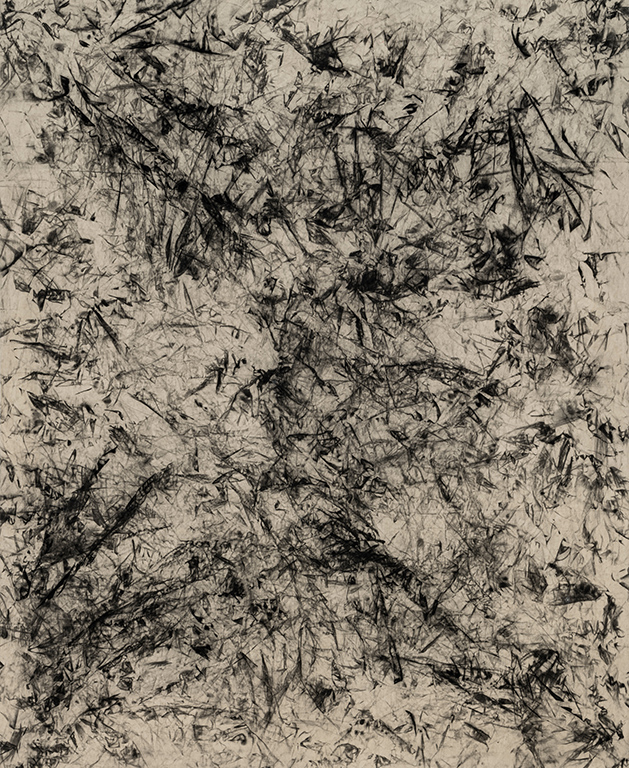

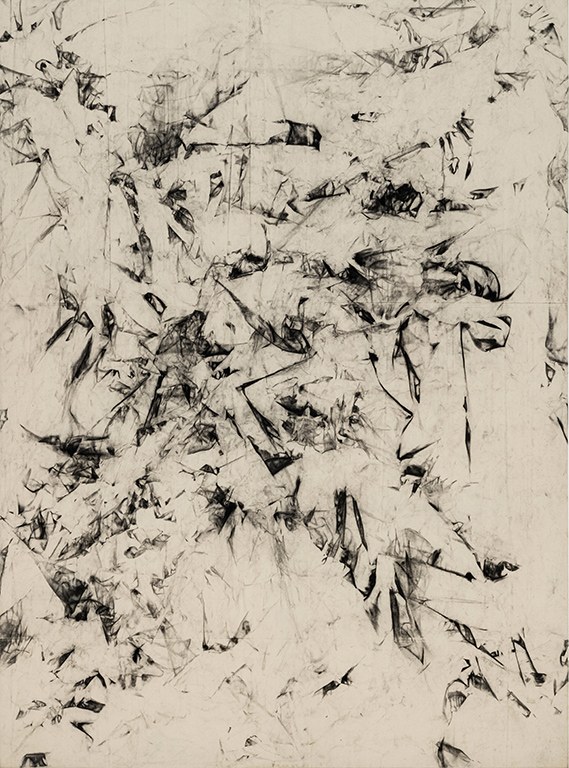

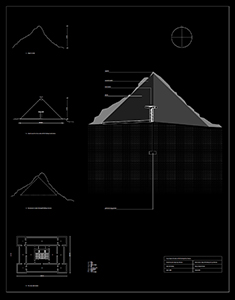

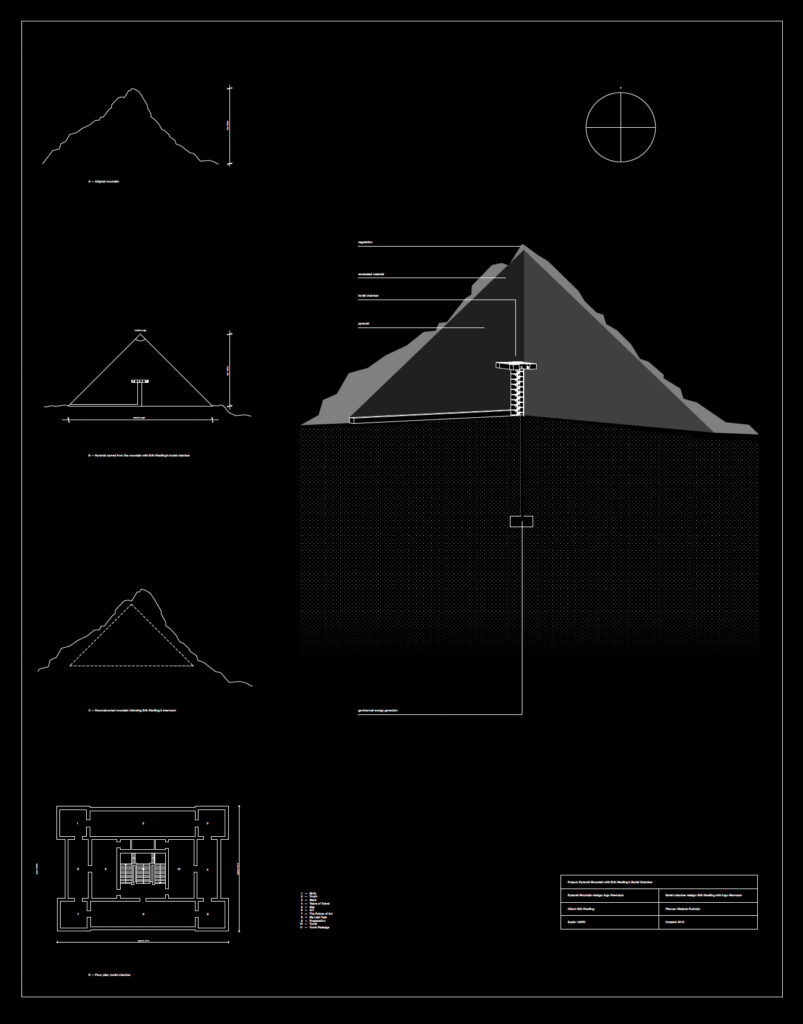

“It is much better, when many images appear strange to the viewer for a time ... ” —Ernst Fuhrmann, “Überblick”(1) 1. It is among the peculiar paradoxes of photographic history that the aesthetic of external appearances, for which the photography of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) became known, started out with barbs—more precisely with cactus barbs. Even if this aesthetic was often exclaimed as sleek, cool, or even as a transfiguration of the world of things and goods, at the beginning, it seemed to be much more thorny, resistant, abrasive, natural, and yet formally perfect—and precisely that was its aesthetic fascination. Plants have been among the preferred objects of photography from the very start, appearing as subjects since the earliest times, as in the photographs in William Henry Fox Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature or the comprehensive photographic archival works of Anna Atkins in the eighteen-forties, but since then are mainly being used as objects of still life photography. This doesn’t change until about the turn of the century, when photographic floral patterns come into wide use in fine arts and architecture (think of the floral ornaments of the Jugendstil and Art Nouveau). Karl Blossfeldt, who, ultimately, also stems from this tradition, presented a classic work of Neue Sachlichkeit photography in 1928 with his book, Urformen der Kunst. Even when Blossfeldt still represents the crossover point of very different lines of tradition that range from the monism of a Haeckel and the biosophy of a Fuhrmann, to the peculiar biological theory of a K. H. Francé, and classical photographic documentation for artistic use and art education, his photographs of plants set the course for a new way of observing a classical object. And they were reviewed as such: Walter Benjamin, for instance, devoted an important review to Blossfeldt as a turning point in photography in his work Kleine Geschichte der Photographie. Georges Bataille published an essay, “Le langage des fleurs,” in his magazine Documents with Blossfeldt’s photographs. Surrealists reviewed them with enthusiasm and even popular magazines, such as Uhu, referred to the images. There in the article, “Grüne Architektur,” a photograph of a horsetail was compared with architectural photographs. This was also shown in a similar fashion in a variety of forms in historical and theoretical architectural works. Many further examples could be mentioned. Plant photography did move into the focus of attention for a short period of time and acted as a programmatic determining factor between art, technology, and form. Form follows function: this defined position of modernity is already found implemented by plants in an exemplary manner. Images of plants held a special meaning and an unusual objective; it was about nothing less than the basic forms of nature and of culture. As Karl Nierendorf wrote in the foreword of Blossfeldt’s Urformen, it is about “grasping the deeper meaning of our times which in all areas of life, art and technology strives towards recognition and realization of a new unity.(2) Plants become the archetype and the photography that documents it, a universal medium. While cacti play a comparatively marginal role in Blossfeldt’s Neue Sachlichkeit photographic Florilegium, they move into the spotlight of Albert Renger-Patzsch’s work, the second important figure of Neue Sachlichkeit photography. Here, as well, we find a programmatic connection of images of plants and a formal new definition of modern art. As Carl Georg Heise wrote in his introduction to Albert Renger-Patzsch’s epochal illustrated book, Die Welt ist schön: “The photograph releases the characteristic section out of the multiplicity of guises, underlines the essential, omits that which seduces into digression. It holds the observing gaze firmly spellbound on the strangely beautiful organic growth. It clarifies what the scientist can only describe. It shows the appeal of the substantial: as in the matt glaze of grape skin or the delicate hair on the calyx of the echynopsis cupreata. The beauty of color: one can feel the somewhat intrusive brilliancy of the dahlia, that must assert itself in the colorful autumn, the forceful expressiveness of individual forms: the euphorbia grandicornis cuts through the dark surface like a jagged flash.”(3) The photograph of the euphorbia grandicornis, a type of cactus discussed here, is among the most famous photographs of Albert Renger-Patzsch. It is reproduced in Die Welt ist schön, and is thus part of a proper aesthetical program, but originated in connection with a comprehensive documentation of plants and here, specifically, of cacti for the Folkwang/Auriga publishing house. From 1922 to 1925 Renger-Patzsch produced hundreds of images for contracted freelance work.(4) Between 1924 and 1931, four volumes of the series, Die Welt der Pflanze were published in which a preference for the prickly flora world was striking: Orchideen (1924), Crassula (1924), Kakteen (1930), and Euphorbien (1931). The last two volumes of this series stem explicitly, as the cover already shows (fig. 1), from the darkroom of Walther Haage—as well as those images that are the starting point and material basis of this series from Erik Niedling. Hence, Walther Haage continues a series, to which Renger-Patzsch and others made significant contributions. Here, the leader was the dazzling figure of Ernst Fuhrmann, who in 1931 published a selection of photographs from the Folkwang/Auriga archives in a volume titled Die Pflanze als Lebewesen. The introduction of this volume called “Überblick,” tries to describe in a few, somewhat enigmatic short pages, the difference between flora and fauna, plants and animals and ultimately also the difference between them and the world of humans. In the “extraordinary world of appearances,” so Fuhrmann, those that possess “the small ability for abstraction” can perceive and recognize that “animals and plants are in a continual interaction with each other” and even in the assumed trivial appearance of a leaf, a downright “state building individual of the plant” can be determined. This observation is so important to Fuhrmann that he repeats it: “A plant is a state. Its individuals have totally different duties to fulfill. Some operate in the ground, others are effective in the stem and bark and again others evolve, while some have to perform a continual service, such as the tendrils, etc.” Behind the photography of plants is a proper aesthetic-philosophical program that finds visual abbreviations of complex cultural attempts at meaning in plants. The plant is a miniature world and the photographs show in the “appeal of the composition” just those sought and found self-evident structures, that in the world of everyday life are no longer taken for granted: “In our photographs, we have found the beautiful forms of plants to be self-evident, endlessly variable, yet always perfect.”(5) Die Welt der Pflanze is in many ways our world and the photographs should be seen as such—not only as an archetype of art, but also as an archetype of nature and culture, flora, fauna, and also technology and art. The Neue Sachlichkeit photographer, Albert Renger-Patzsch, was more reserved, but nevertheless enthusiastic. His elation for plants and especially for images of cacti can not only be seen by the fact that he published several texts on exactly this topic,(6) but also by their restrained programmatic trait, that interlocks technology and perception. “The impression of a collective vegetal force that is found in most forms of cacti, is in itself worth a plate,” as it says laconically in his article “Kakteen-Aufnahmen” for the magazine Photographie für alle. And in his essay on the “Photographieren von Blüten,” he establishes a special reference to the perception of an object: “The charm” in the photography of plants consists of the fact that one is “forced to adjust one’s eyes to the more or less small organism that constitutes a flower, that one is forced to see with the eyes of an insect and, for once, to make their world ours.”(7) The photography of plants in general, and especially of cacti, holds a special place in photography and modern art: here not only a revolution of perception is shown en detail, a “new way of seeing,” but also a proper aesthetic-cultural theoretical program. The plant and cacti images sustain an old ceremony: that of a reconciliation of culture and nature through art. 2. Erik Niedling’s work, Formation, is a special form of repetition: it brings back tradition and repeats tradition, but transforms this reconstruction through a subtle arrangement in its deconstruction. The recurrence of the images throughout the work registers a difference in and with the images—in the only assumed identical material. In the studio, almost secretly, negatives are transformed into positives that only look as if they are negatives. The original manipulations, the retouching and the corrections, are still visible—and last but not least, they appear to shine, although they come out of the darkness. The function of the enlargement of the plant images that played a central role in the photography of the Neue Sachlichkeit is taken over here through this transposition of the negative. It produces a new perspective that alienates the seemingly familiar, morphs, and transforms. In this way, Erik Niedling creates images that visually transcribe the ambivalence of the Neue Sachlichkeit’s visual program and still remain loyal to the factual unemotional approach of the photographs used. He generates a visual tilt that leads to the unanswerable question, what is it about now: about positive or negative, documents or works of art, historical material or his artistic recreations. At the same time, that is precisely what it is about: positive and negative, documents and works of art, historical material and its recreation. New images for an old ceremony, that is no longer the same. Erik Niedling’s Formation repeats photographic history as cultural history and cultural history as photographic history. The starting point is generated by the cactus culture, together with its most important characteristic or to be more exact, that of its photographic documentation, which for its part registers the complex history of the discovery of the cactus as a privileged object of the photography of the Neue Sachlichkeit and its cultural program: complex cultural history (and histories). In many ways, it is about a determined cultural history and, as we have seen, the stakes are always high: yes, a downright revolution of the nature of perception and thought. This subtle repetition of a cultural history as photographic history is due to a certain discovery or better yet, several discoveries. Everything began when a volume from the series, Die Welt der Pflanze was tracked down in the library of the Angermuseum in Erfurt, in which the photographs of the Erfurt-based photographer and nursery owner, Walther Haage were printed. The garden center still exists today, and when Erik Niedling went there he discovered something of a camera obscura, a dark room in the attic of the apartment house where photographs were hidden to protect them from later access. The locked room was opened and a large wooden box was brought to light containing hundreds of negatives from Walther Haages’ estate that documented the work of his own cactus culture, and that were probably also used for advertising and publication purposes. These negatives constitute the material for Erik Niedling’s photographic works, who, for his part, spent weeks archiving, securing, studying, printing, arranging, grouping, and spreading out the plates to then transform several of them into new large-format prints. This photographic metamorphosis of the photographic plates also brought about—in a wondrous way—the metamorphosis of the objects. The physical reproduction of the original glass negative plates also transformed the material because Erik Niedling remained true to the sober objectivity of the given material. He again repeated the transformation that the photographers from the period between the wars strived toward and made the photographic language of form legible as a program—and that sometimes in a literal sense: scissors, knifes, blades, and garden tools refer not only to the cacti culture, but also to the cultural encryption of photography that has always been a process of cutting, cropping, and caesura. The work on the cacti is at the same time metaphorical, but also highly specific work on and with photography. This also applies to the serialized arrangement of cacti, earthenware, and pots, that correspond to a serialized arrangement of photographs, or for the archive wall, in which seeds and samples are stored (and in which photographic archives could also have found their place and perhaps even have). And last but not least, for the allotted use of light without which no cactus culture and also no photograph could be successful. The same thing is repeated on the level of the image: the manipulation—meant here in the literal sense—of the cacti is doubled in size through manipulation of the negative plates, which are recognizable on the enlargements from the C- prints in a sometimes irritating way. This brings us to the old question of the objectivity of photography, but at the same time photography is identified as a reproduction, as a process of manipulation. In one photo the word, wetterfest (weatherproof) can be seen on a pencil that is supposed to make the scale of the blades discernible. But here it becomes a light sensor in that it underlines what the image is showing—because wetterfest is not that what Johann Faber produces, but instead what homo faber produces: images upon images, images of reflection, that make complex cultural history readable. Erik Niedling succeeds in creating something wonderful and at the same time highly alienating: he forces the aesthetic-epistemological program out of the Neue Sachlichkeit photographs and leaves them in an idiosyncratic twilight—in the hauntingly beautiful and darkly luminous light of photography. And in this light, our cultural history begins to shine anew. [BILD] The reproduction is taken from: Rainer Stamm’s Die Welt der Pflanze. Photographien von Albert Renger-Patzsch und aus dem Auriga-Verlag (Ostfildern-Ruit, 1998), p. 16. Notes 1 Ernst Fuhrmann, “Überblick”, in idem. Ed., Die Welt der Pflanze (Frankfurt am Main, 1931). 2 Karl Nierendorf, “Einleitung,” in Karl Blossfeldt, Urformen der Kunst (Berlin, 1928), p.ix. 3 Carl Georg Heise, “Einleitung,” in Albert Renger-Patzsch, Die Welt ist schön (Munich, 1928), pp. 7f. 4 A comprehensive and detailed documentation of the images from Renger-Patzsch can be found in Rainer Stamm, Die Welt der Pflanze. Photographien von Albert Renger-Patzsch und aus dem Auriga-Verlag (Ostfildern-Ruit, 1998). 5 Gert Mattenklott ventures a depiction of this program in several publications. Compare with the beautiful documentation of Karl Blossfeldt’s plant photographs: Karl Blossfeldt. Urformen der Kunst. Wundergarten der Natur. Das fotografische Werk in einem Band, with a text from Gert Mattenklott (Munich, et al, 1994). As to Fuhrmann, see Mattenklott’s “Nachwort,” in Ernst Fuhrmann, Was die Erde will (Munich, 1986), pp. 237–55, and “Vorwort,” in Ernst Fuhrmann, Neue Wege, vol. 10 (Hamburg, 1983), pp. i–ix. 6 See these texts by Albert Renger-Patzsch: “Pflanzenaufnahmen,” in Deutscher Camera Almanach, vol. 14 (Berlin, 1923), pp. 49–53; “Das Photographieren von Blüten,” in Deutscher Camera Almanach, vol. 15, (Berlin, 1924), pp. 104–12; “Kakteen-Aufnahmen,” in Photographie für Alle, no. 6 (Berlin, 1926), pp. 83–86; “Photographische Studien im Pflanzenreich,” in Deutscher Camera Almanach, vol. 17 (Berlin, 1926), pp. 137–41; and “Pflanzenaufnahmen im Winter,” in Camera (Luzern, January 1927) pp. 186ff. 7 Renger-Patzsch 1924 (see note 6), p. 105. In: Formation, ZERN (Hrsg. / ed.), Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern 2008